Navigating Menstruation: Support for Caregivers of Individuals with Disabilities

➡️ Download this guide as a PDF

Preface

This resource is not meant to replace medical advice from a licensed healthcare provider. Each child has unique needs and the people best equipped to respond to those needs are you and the child’s provider(s). This resource includes a wide range of information and is meant to be something you can revisit over time as needed.

Menstrual cycles are an important step in a child’s development and a typical part of life for those assigned female at birth. Attitudes surrounding menstruation vary widely across cultures, genders, and communities, and experiences with menstruation are different for every person. Mood changes, behavioral issues, and uncertainties about how to discuss periods are just a few of many common difficulties for children and caregivers navigating this life transition.

When your child has a disability, this can be even more complicated to navigate. While gathering information on menstruation for families with neurodevelopmental disabilities, we noticed a lack of comprehensive resources. This observation was echoed by members of our Simons Searchlight Community Advisory Committee.

The goal of this guide is to address some of the very real anxieties and concerns that caregivers of children with neurodevelopmental disabilities have surrounding this topic. This includes children with autism, intellectual disability, and epilepsy. We hope that this resource can help to fill the gap by providing easily accessible information that serves as a guide for you to successfully navigate this stage in your child’s life.

Anticipating menstruation-related needs before they arise can help to prepare you and your child for the challenges you might face. If your child is already menstruating, we hope that this guide provides new perspectives or tips, and we welcome any feedback on how to make it more useful to you.

Topics and resources in this guide:

- Overview and definitions of puberty and menstruation

- Unique challenges those with neurodevelopmental disabilities face with menstruation and tips on how to navigate those challenges

- Practical tips and strategies, including how to communicate about menstruation with your child

- Choosing menstrual products, including examples of products geared towards those with mobility considerations

- Menstrual hygiene and hormonal birth control

- Appendix of resources, including disability-focused women’s health clinics and resources on menstruation

Expert guidance and community collaboration

In creating this resource, the Simons Searchlight team developed a framework grounded in research, community feedback, and clinical expertise. We are deeply grateful to the experts who contributed their time and insight:

- Wendy Chung, M.D., Chief of Pediatrics at Boston Children’s Hospital and Co-Principal Investigator of Simons Searchlight

- Amanda Jacobs, M.D., Chief of Adolescent Medicine at Boston Children’s Hospital

- Keely Lundy, Ph.D., Assistant Professor, Center for Development and Disability SOM – Pediatrics

- Cora Taylor, Ph.D., Co-Principal Investigator of Simons Searchlight and Clinical Psychologist at Geisinger Autism & Developmental Medicine Institute

We also extend a heartfelt thank you to our Community Advisory Committee members – April Canter, Alida James-Fenner, Christie Abercrombie, Alexandra Lee, Cheryl Richt, Rebecca Dolan, Amy Fields, Delf, Genesis Romo-Raudry, and Stacy Hanna -for helping curate this guide and ensuring it reflects the real needs, questions, and voices of our community.

Understanding Puberty and Menstruation

Puberty

Puberty is the time in which a child starts to develop adult characteristics. In girls (those assigned female at birth), puberty usually starts between 8 and 13 years of age. This guide from the Cleveland Clinic has more information on puberty in boys and girls and can give you a better sense of what to look out for as your child goes through the mental, physical, and emotional changes associated with puberty (Cleveland Clinic, 2024).

Physical signs of puberty in girls:

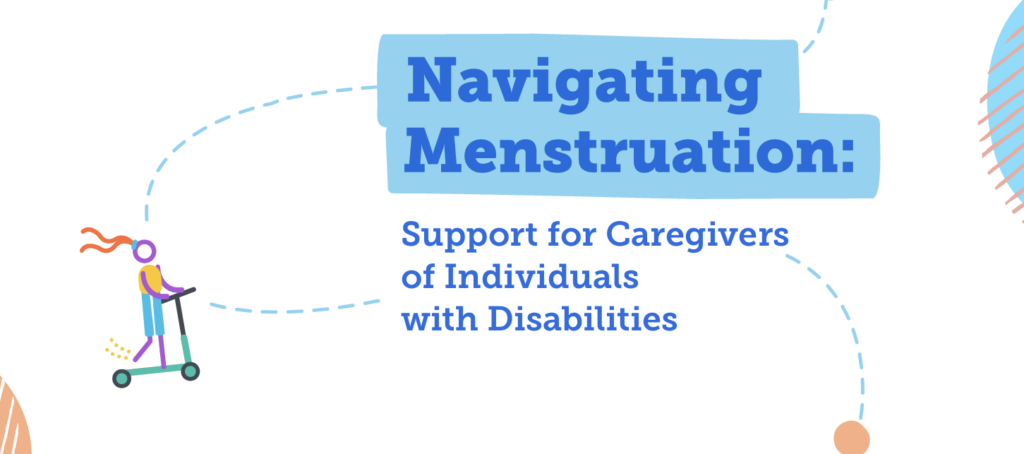

- Breast development

- Breast buds, which are small lumps or discs beneath the nipple, are often the first sign (Seattle Children’s Hospital, 2025).

- Menstrual periods start about 2 years after initial breast bud development (Allen & Miller, 2019)

- Underarm and pubic hair

- Acne

- Growth spurts

This is what breast development often looks like (“Breast Development,” n.d.).

Many of these changes come with new sensations. For example, breast buds might be sensitive or painful; your child might pick at acne; or coarse hair might be a source of texture aversion.

Early onset of puberty, typically before 7 to 8 years old for girls, is called precocious puberty. Of 1,184 females with genetic conditions in Simons Searchlight who submitted medical history data, 34 reported a diagnosis of precocious puberty (2.9 percent).

Late onset of puberty, typically after 12 to 13 years old for girls, is called delayed puberty. Of 1,184 females with genetic conditions in Simons Searchlight who submitted medical history data, 8 reported a diagnosis of late or delayed puberty (less than 1.0 percent).

If you notice signs of puberty in your child before or after the typical age range of onset, please be sure to bring this up with your child’s doctor. They might refer you to an endocrinologist, adolescent medicine specialist, or obstetrician/gynecologist (OB/GYN).

Puberty Preparedness

Your child may experience physical, behavioral, and emotional changes during puberty, and understanding or navigating these changes together may require special attention. The SPARK for Autism webinar by Cora Taylor, Ph.D., offers comprehensive tips on how to prepare for puberty in individuals with disabilities (Taylor, 2022).

disabilities (Taylor, 2022).

This Vanderbilt Kennedy Center handbook provides resources on how to prepare for puberty for girls with intellectual disabilities (Vanderbilt Kennedy Center, 2021).

Discussing puberty and related topics can be uncomfortable, but it is important to start having these conversations early and often. Establish yourself as a safe and trusted resource, be mindful of your child’s learning needs, and lean on your child’s providers for information, resources, and other support.

Menstruation

There are often a lot of complex emotions surrounding menstruation. Your child’s first period can be scary for everyone involved. Some of our Simons Searchlight community caregivers have reported feelings such as dread, concern, fear, and anticipation. This is normal, but it does not need to be a negative experience.

According to the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG), the age at which girls get their first period, also known as menarche, is around 12 years. This might not be the case for your child — many medications and medical conditions can affect when a first period happens. If your child has experienced other signs of puberty but has not had their first period by age 15, she might have a condition called amenorrhea. In this case, ask their doctor for a referral to a specialist (American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 2015).

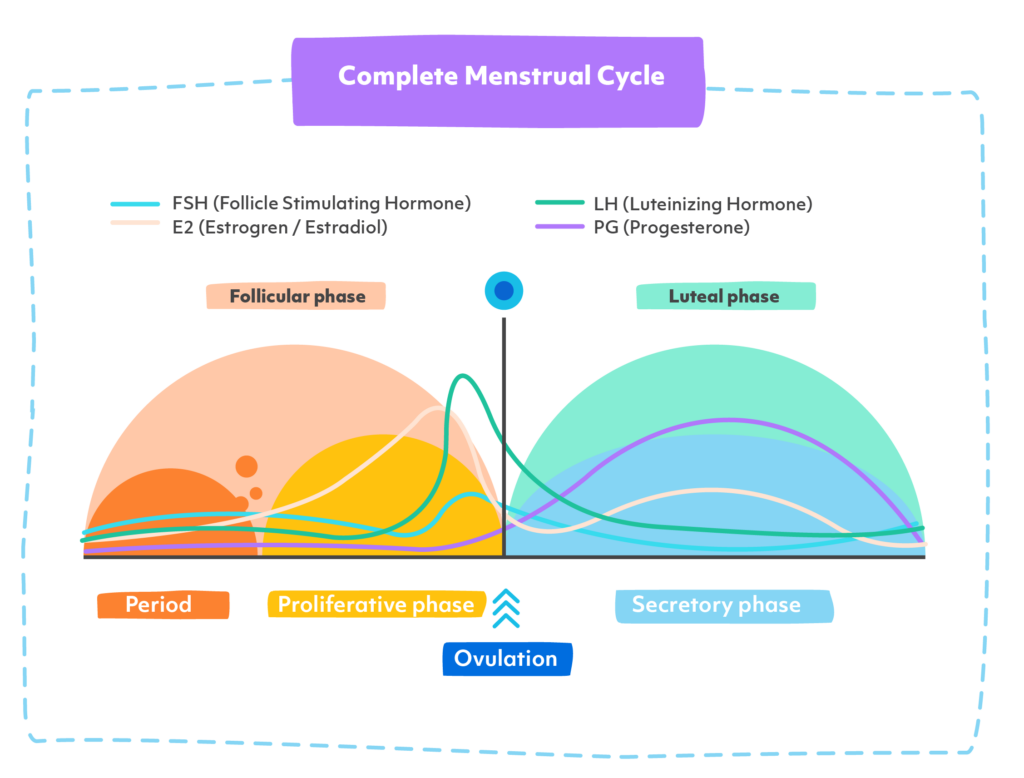

The menstrual cycle has four phases: the menstrual phase, follicular phase, ovulation, and the luteal phase. A typical cycle lasts around 28 days, though this can vary from person to person. Each phase is influenced by changing levels of hormones, including follicle stimulating hormone (FSH), luteinizing hormone (LH), estrogen, and progesterone (Cucci, 2024).

- Menstrual phase (Days 1–5): This is when bleeding occurs as the uterine lining is shed. Hormone levels are at their lowest.

- Follicular phase (Days 1–14): Overlaps with the menstrual phase at the beginning. The body prepares an egg for ovulation. Estrogen starts to rise.

- Ovulation (Days 14–17): Triggered by a surge in LH and FSH, ovulation is when an egg is released from the ovary. This is the most fertile time in the cycle.

- Luteal phase (Days 15–28): Progesterone and estrogen rise to prepare the uterus for a possible pregnancy. If no fertilized egg implants, these hormone levels drop, leading to the next period.

Below is a diagram of the menstrual cycle with lines that represent hormone levels (“Menstrual cycle timeline,” n.d.). FSH and LH peak just before ovulation, while estrogen and progesterone increase just before the menstrual period. Caregivers might notice certain changes at different times of the cycle, such as changes in mood that are associated with hormonal changes.

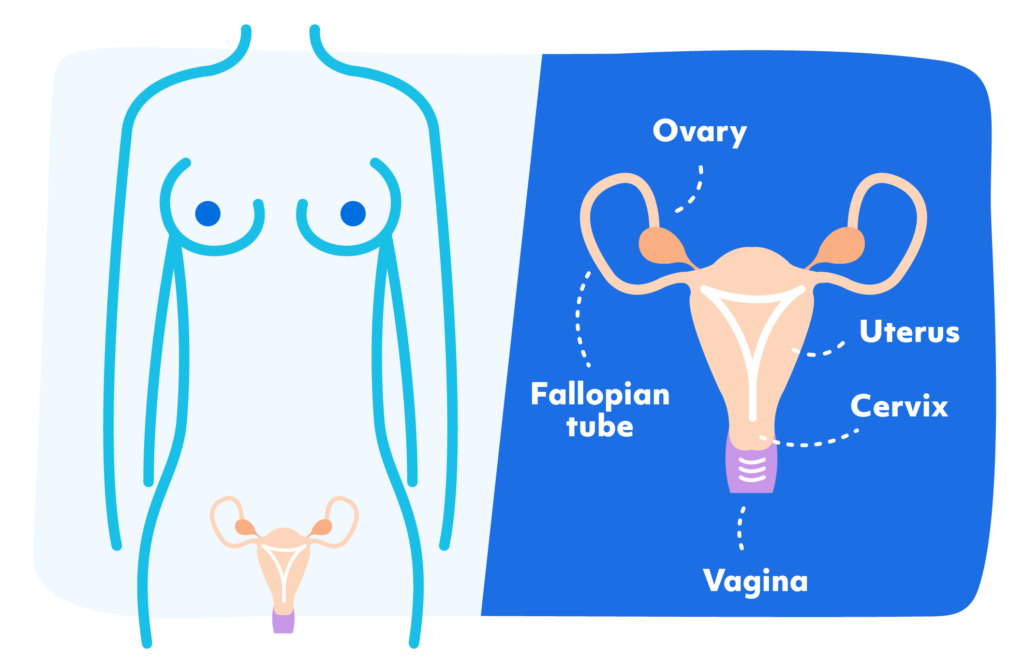

To better understand how the menstrual cycle works, it can be helpful to look at the diagram below of the reproductive system (Ignite Healthwise, LLC, 2024). The key parts involved include:

- Ovaries – where eggs and important hormones are made

- Fallopian tubes – which carry the egg from the ovary to the uterus

- Uterus – the organ where a fertilized egg could grow into a baby

- Endometrium – the inner lining of the uterus that builds up each cycle

- Cervix and vagina – the lower parts of the reproductive tract, through which menstrual blood exits the body

The lining of the uterus (endometrium) builds up throughout the cycle in preparation for the arrival of a fertilized egg. If no fertilized egg arrives, this lining is shed through the vagina over a period of 3 to 7 days. This is known as the menstrual period.

During the first menstrual period and the first year or so afterward, the length and heaviness of bleeding may vary. This is completely normal. However, it’s a good idea to talk to your child’s doctor if you notice things like unusually painful periods, irregular cycle lengths, or significant mood or behavioral changes.

Unique Challenges

Preparing for menstruation and adjusting to the changes that come with it take time, trial and error, and patience. While you cannot always predict the challenges your child will face, tracking menstruation, mood, behavior, and activity throughout the menstrual cycle can help you gather the necessary information to identify possible patterns. If you find these patterns concerning, your notes will help you discuss your concerns with your child’s provider. Encourage your child to participate in tracking their cycle and associated changes if they are able. This will help them to draw associations between their menstrual cycle and any symptoms they might be experiencing.

Based on research and feedback from our Community Advisory Committee, we have compiled three major categories of challenges that may be most relevant to people with neurodevelopmental disabilities: sensory issues, catamenial epilepsy, and mood and/or behavioral changes. The sections below also contain suggestions for how to address these challenges.

1. Sensory Issues

Menstruation comes with many new sensations, sights, smells, and sounds (Steward, 2018).

Keely Lundy, Ph.D., highlights that aversion or exploration of these new sensory experiences might include new behaviors, such as touching, tasting, or smearing menstrual blood; removing menstrual products; or refusing the application of menstrual products in public or outside of a bathroom (Lundy et al., 2024). Although these behaviors can be alarming for a parent, keep in mind that they are simply ways of exploring and adjusting to new sensations. Having conversations about and teaching or reinforcing appropriate behavior for certain settings can help to address concerns. These conversations can be facilitated and reiterated by therapists, counselors, and doctors as appropriate. Amanda Jacobs, M.D., stresses the importance of sharing any concerns about menstruation—including behavioral changes—with your child’s healthcare provider, as they often have helpful resources and strategies. It can also be useful to share the tips or tools that work for your family with teachers and other caregivers, so everyone can support your child consistently. Below are some concrete strategies that you might find helpful.

smearing menstrual blood; removing menstrual products; or refusing the application of menstrual products in public or outside of a bathroom (Lundy et al., 2024). Although these behaviors can be alarming for a parent, keep in mind that they are simply ways of exploring and adjusting to new sensations. Having conversations about and teaching or reinforcing appropriate behavior for certain settings can help to address concerns. These conversations can be facilitated and reiterated by therapists, counselors, and doctors as appropriate. Amanda Jacobs, M.D., stresses the importance of sharing any concerns about menstruation—including behavioral changes—with your child’s healthcare provider, as they often have helpful resources and strategies. It can also be useful to share the tips or tools that work for your family with teachers and other caregivers, so everyone can support your child consistently. Below are some concrete strategies that you might find helpful.

There are a few ways for parents to help ease sensory challenges, even before menstruation starts. Lundy and Taylor suggest practicing wearing menstrual products ahead of time, or exploring different menstrual product options before your child’s first period. This might include:

- Allowing your child to play with pads, tampons, and other menstrual products and practice using or wearing them.

- Finding which product works best for your child is a process. Across the providers and community members we spoke to, absorbent underwear—often called “period panties” in the U.S. and “menstrual underwear” or “period knickers” in some parts of Europe—came up frequently. According to Lundy, using a heavy-flow option minimizes the number of times the panties need to be changed, and an antibacterial or odor-defense option can help reduce smell-related sensory challenges. See the “Menstrual Hygiene” section below for recommended products.

- Having conversations with your child beforehand about appropriate behavior and things to expect during their first period.

- Having a stimming toy, sensory toy, or comfort item on hand during the period.

- Keeping an eye out for menstrual pain and being proactive with remedies, such as a heat pad and over the counter pain relief medications. Please be sure to note any signs or mention of unusual pain levels and let the child’s provider know so that they can help figure out if something abnormal is going on.

2. Catamenial Epilepsy

Catamenial epilepsy is a type of epilepsy in which seizures are related to menstruation (Cedars Sinai, n.d.). About 40 percent of women with epilepsy experience catamenial epilepsy (Maguire & Nevitt, 2019). This type of epilepsy has 3 main patterns:

- C1 – increased number of seizures during the menstrual phase, from days 1 to 5 of the period

- C2 – increased number of seizures during ovulation, around day 14 of the cycle

- C3 – increased number of seizures in the luteal phase, from days 15 to 28 of the cycle

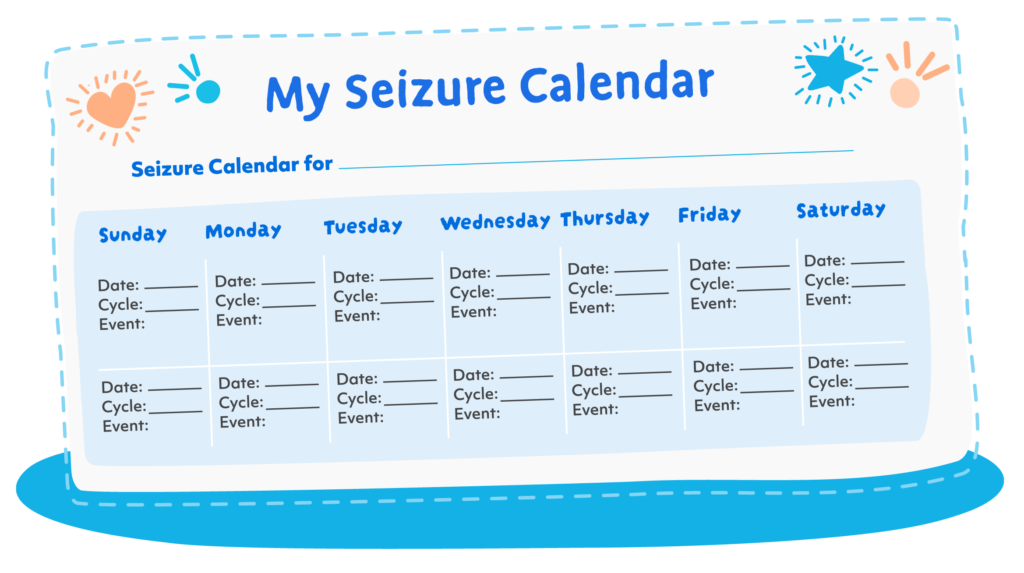

If your child experiences seizures, be sure to track them using a seizure calendar. This calendar (see below) can help you understand whether seizures are related to your child’s monthly cycle (Epilepsy Foundation of America, 2019).

Note. From “My Seizure Calendar,” by Epilepsy Foundation of America, 2019. (https://www.epilepsy.com/sites/default/files/atoms/files/720MSC_MySeizureCalendar_05-2019.pd

Seizure management should be done with your child’s neurologist or specialist. This might include adjusting seizure medication scheduling or dosing, hormonal therapy or birth control, or in some cases, surgery. The best treatment option depends on several factors that you can discuss with your child’s neurologist or specialist (Cedars Sinai, n.d.).

One concern that many parents have is the interaction between anti-seizure medications and hormonal birth control. Jacobs recommends asking the doctor if they are comfortable with prescribing these medications together. If not, Jacobs suggests seeing a specialist, such as an adolescent medicine provider or OB/GYN, and/or asking your child’s neurologist.

3. Mood and/or Behavioral Changes

Mood and behavioral changes are a normal part of puberty and menstruation. Your child might experience these in a unique way based on any existing mood and/or behavioral issues, their ability to emotionally self-regulate and self-soothe, and their individual experience with menstruation.

It is important to note the changes that your child experiences when they happen, and to discuss them with your child and their provider if you are concerned.

Two key conditions associated with mood and/or behavioral changes around menstruation include premenstrual syndrome (PMS) and premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD). PMS is very common, even among people without a neurodevelopmental disability. PMDD is less common, affecting about 3 to 8 percent of women (Halbreich et al., 2003). It is unknown how common these conditions are in people with neurodevelopmental disabilities and autism, but some sources suggest that they might occur at increased rates (Miura & Hashimoto, 2023).

Premenstrual Syndrome

Around menstruation, your child might show signs of PMS. The most common symptoms in neurotypical people are headaches, bloating, and mood changes, but other symptoms like breast tenderness, cravings, fatigue, and mood and behavioral changes are common as well (Office on Women’s Health, 2025; Mayo Clinic, 2022). These symptoms are common in those with neurodevelopmental disabilities, but the degree of severity can vary. Your child might experience more extreme or subtle degrees of changes in some or all of the above ways. Studies have found that those with neurodevelopmental disabilities tend to be more uncomfortable before menstruation begins, have depressed or hopeless moods, and experience higher levels of anxiety and tension than their neurotypical peers (Miura & Hashimoto, 2023).

Consider these strategies:

- Educating and explaining the causes of behavioral changes to promote understanding

- Providing comfort items, such as favorite snacks and toys

- Doing fun activities to provide distraction

- Doing physical activity, managing stress, and keeping a healthy lifestyle through diet, exercise, and sleep (Tracy et al., 2016)

Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder can be thought of as a more severe form of PMS (Mayo Clinic, 2019) . Whereas PMS might be inconvenient, PMDD can cause major disruptions to one’s life. The core symptoms of PMDD include mood swings, anger, depression, and anxiety (Clay, 2023).

According to Jacobs, it is especially important to keep an eye out for PMDD if your child cannot effectively communicate how they feel because there might be a tendency to minimize the possibility of PMDD in these instances. It might also be difficult to tell the difference between existing conditions (anxiety or depression) or severe behaviors and PMDD.

One key aspect of PMDD is that it is strictly associated with the menstrual cycle — the symptoms appear just before menstruation and go away in the days following menstruation (Clay, 2023). Depending on the symptoms, PMDD is usually managed by hormonal birth control, antidepressants, and/or changes to lifestyle, diet, and exercise (Johns Hopkins Medicine, n.d.).

If you suspect PMS or PMDD, you should track changes to behavior and mood on a calendar, and note any association with menstruation. Making note of any new behaviors in this way can help you to more easily identify any concerns. Please be sure to discuss these concerns with your child’s doctor, who can provide the best support and individualized suggestions.

Menstrual Hygiene

There are many menstrual hygiene options, including tampons, pads, cups, period underwear, reusable pads, discs, reusable cloth pads, and more. Ultimately, choosing the right product will take some trial and error, and often depends on your child’s mobility and sensory needs.

Overall, Taylor and Lundy suggest period underwear as a great option to minimize potential sensory issues and for its ease of use. Period underwear, also called period panties, is like regular underwear, but contains built-in features to absorb menstrual blood, much like a pad, without the added process of removing and disposing of a stick-on product. During your child’s period, they can use a pair of period underwear the same way they would use a normal pair of underwear. Once the underwear is saturated, it can be changed out for a fresh pair, and the used pair can be rinsed, and then cleaned in a washing machine. Note that care instructions vary by product, and there are also disposable period underwear options.

Typically, period underwear should be changed every 12 hours, or more frequently depending on flow volume. If your child has mobility considerations, there are options with Velcro and loops. Although Simons Searchlight does not endorse specific brands, we have compiled a list of some options that might be a helpful starting point (see below).

Be aware that period products are expensive, especially period underwear. But, keep in mind that reusable underwear can last anywhere from 6 months to 2 years (Sreenivas, 2025).

Note that in the U.S., menstrual products are HSA/FSA-eligible as of March 2020 due to the Cares Act. Here is a guide with more information on how to pay using a health savings account or a flexible spending account (“How to Buy Period Products With Your HSA/FSA Insurance,” 2021).

Menstrual Underwear Options

Mobility Considerations

Some brands offer adaptive period underwear styles that may be more comfortable or easier to use for individuals with mobility challenges, including those who use wheelchairs. These products often feature side openings, easy fasteners, or fabric designed for seated comfort.

- Modibodi – Offers a range of absorbencies and styles, including an adaptive style designed with mobility in mind (Modibodi AU, n.d.).

- Period. – Offers inclusive styles, such as adaptive designs that may be helpful for people with mobility concerns (The Period Company, n.d.).

- Liberare – Specializes in adaptive clothing and offers period underwear styles like boy shorts and bikinis designed for accessibility (Liberare, n.d.).

Other Popular Brands

These brands also offer a range of styles and absorbances to suit different needs. They may not have adaptive features, but they are commonly recommended by families and providers:

- Thinx (Thinx Inc, n.d.)

- Aerie Real Period (Aerie, n.d.)

Hormonal Birth Control

Hormonal birth control can feel like a scary or overwhelming topic to bring up with your child’s doctor. While many people associate it only with preventing pregnancy, some families consider it for other medical reasons – like regulating periods, reducing pain, or managing certain hormonal symptoms. It’s completely normal to have questions or concerns, and it’s important to talk them through with your child’s doctor.

There is a common misconception that birth control will result in complete menstrual suppression, such as having no periods or a reduced frequency of periods. This is not always the case. There are a variety of birth control options that include different hormones that can address different needs, such as intrauterine devices (IUDs), implants, shots, rings, patches, and pills (Kaunitz, 2024).

Another common misconception is that menstrual suppression is unhealthy and unnatural, or will permanently affect future fertility. Jacobs explains that many of the hormones used in these methods are already naturally produced by the body, and there are many states in which the body naturally suppresses menstruation, such as during lactation.

Ultimately, finding the right hormonal birth control for your child will require conversations with their doctor and with your child, if they are able to express themselves. Jacobs notes the importance of tracking menstruation and initiating conversations with a provider early on to ensure that they can help address your child’s needs and goals.

Tips from Jacobs and Taylor

Hormonal birth control uses hormones that are naturally present in the body.

- The effects of hormonal birth control are temporary, not permanent – the body can always be returned to its normal state without affecting future fertility.

- If hormonal birth control is not the right choice, you can always stop using it or adjust it. There are a lot of options, and one size does not fit all!

- It is vital that your child’s doctor discusses all concerns you might have. Personal preferences are important for finding the option that’s right for you.

Practical Tips and Strategies

1. Cycle Tracking

Adolescents often have variable menstrual cycles, which can make it difficult to predict when a period will occur. According to Jacobs, it’s important to alert your child’s provider if their menstrual period lasts for more than 8 days, or if they do not have a period for more than 3 months after starting menstruation.

It can be helpful to track menstruation on a calendar or app. You can note things such as mood and behavior changes; flow volume (for example, number of menstrual products used per day); seizure activity; and physical symptoms, such as breast tenderness or bloating. Tracking your child’s menstrual cycle, especially in the initial stages, can help you see any patterns and ease discussions about any concerns with your child’s provider. If your child cannot express pain or moods, note any increases in irritability, increases in behavioral issues, and changes to eating or sleeping.

The medications your child takes can affect menstruation (frequency of period, length of period, flow volume). If your child’s provider has not already discussed this with you, it is important to initiate this conversation when you notice signs of puberty, even before the start of menstruation, so that you have a better idea of what to expect and can be prepared to make changes as necessary.

2. Communicate Early, Frankly, and Frequently

Taylor stresses that one of the best ways to prepare for when your child begins menstruating is to have conversations with them early and frequently, before menstruation starts. This is an uncomfortable topic for many people, and that is okay. Always remember that there are many resources for you to lean on, such as online videos and pictures that you can use as tools to show your child, as well as other members of their support team, including doctors, school nurses, therapists, and counselors.

Taylor stresses that one of the best ways to prepare for when your child begins menstruating is to have conversations with them early and frequently, before menstruation starts. This is an uncomfortable topic for many people, and that is okay. Always remember that there are many resources for you to lean on, such as online videos and pictures that you can use as tools to show your child, as well as other members of their support team, including doctors, school nurses, therapists, and counselors.

Our Community Advisory Committee and the providers and researchers we interviewed for this resource agreed on the importance of making sure that your child knows who the safe and trustworthy adults are in their environments. Teach your child that they can go to trusted adults to ask questions, express concerns, and seek help.

Using frank, appropriate language (proper anatomy terms) can encourage independence and help your child tell you or other trusted adults if something is wrong. Having multiple conversations allows for more time to understand and ask questions and establishes you as a trusted person to approach with questions or concerns your child might have.

3. Encourage Independence

Independence looks different for everyone, depending on physical and intellectual abilities. Usually, if your child is able to toilet independently, the goal should be to manage menstrual hygiene independently (Taylor personal communication; Tracy et al., 2016). It might take a long time to learn menstrual hygiene, but be patient and encourage independence, as this is an important skill. You can help to facilitate independence and self-management in your child by communicating, demonstrating, bringing in community members for support as necessary, and giving your child a menstrual kit (see below).

4. Use Physical and Visual Aids

Encourage your child to become familiar with various menstrual products. Using pictures, flow charts, and physical demonstrations can be helpful, especially if your child has limited language comprehension. Using a doll or toys to make it more interactive and having hands-on demonstrations, such as opening and putting on a pad, exploring period underwear, or any other menstrual product of choice, can help to build ease and comfort with menstruation and let your child know what to expect.

5. Trial and Error

It’s important to buy menstrual products and try them out before menstruation starts. After menstruation starts, it’s possible that what you initially thought would work does not. Don’t be afraid to try different products, including products with different levels of absorbency. The same goes for strategies to manage any other new things that come up with menstruation.

6. Lean on Your Support Network

Don’t be afraid to bring others into this conversation. Your partner, your child’s doctors, school nurses, therapists, other parents or caregivers of kids with neurodevelopmental disabilities, and other members of your support team can give you tips and help teach and reinforce appropriate behavior.

Always seek support from your community when you need it. There’s a good chance that others are going through similar situations and can help you navigate, or they might have the same questions and can provide support.

This is your child’s first time navigating menstruation, and it’s important to acknowledge that it’s your first time navigating menstruation with them. There is no ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ way to go about the process, but bringing in others will help you feel more supported, empowered, and comfortable with guiding your child.

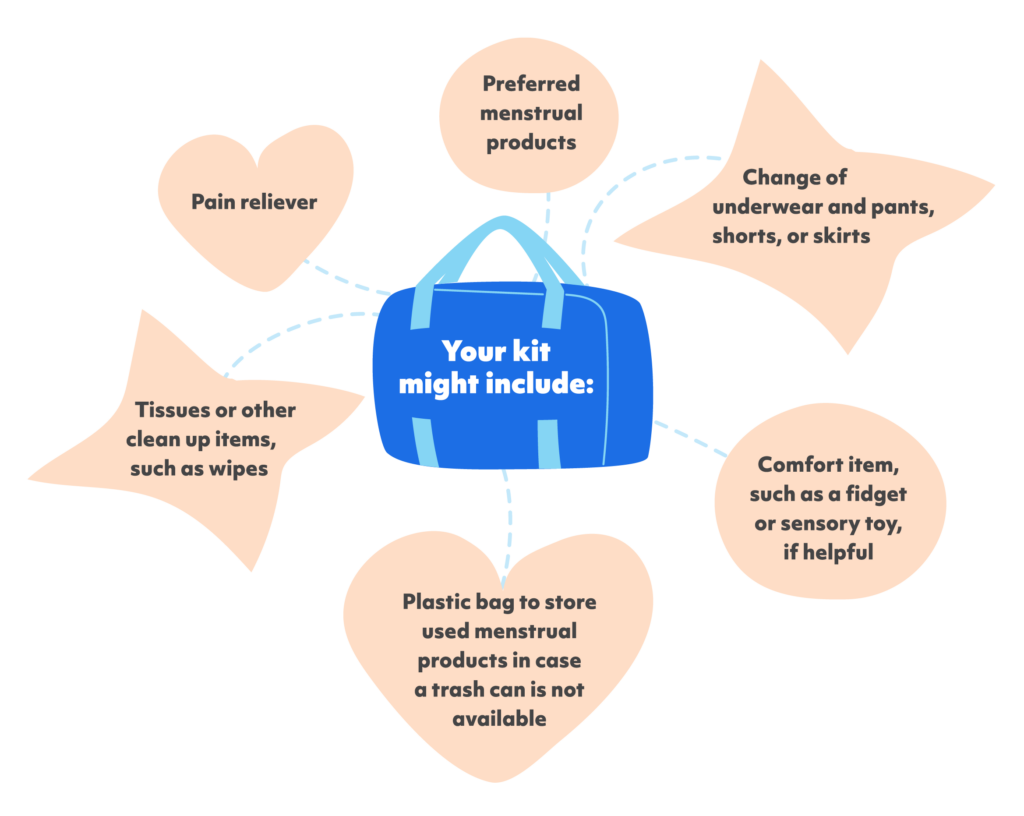

7. Put Together a Menstrual Kit

This is a great resource for any on-the-go emergencies to ensure that you are prepared.

Your kit might include:

- Preferred menstrual products

- Change of underwear and pants, shorts, or skirts

- Pain reliever

- Comfort item, such as a fidget or sensory toy, if helpful

- Tissues or other clean up items, such as wipes

- Plastic bag to store used menstrual products in case a trash can is not available

8. The Doctor’s Office — First Visit After First Period

Your child’s first doctor’s visit after they start menstruating is a good time to bring up any concerns you might have about their cycle, sexual health, and overall well-being. If your child is 18 or older, or is otherwise managing their own health care, consider giving them time to speak with the doctor alone. This can help them build independence and develop a trusting relationship with their provider.

Here are some topics that might come up during your child’s visit to the doctor after they start menstruating:

- Menstrual cycle regularity

- Flow volume

- Menstrual pain

- Behavioral and mood changes

- Assessment of sexual knowledge

- Interest in sexual activity

- Relationship safety education

- Overall well-being (Quint et al., 2016)

9. Seeing a Specialist for Hormonal Birth Control — Pelvic Exams

You might be concerned that a pelvic exam is required to get a birth control prescription. In most cases, especially for people under 21, a pelvic exam is not needed to prescribe hormonal birth control – unless there are specific symptoms or concerns the provider wants to look into. You can ask about this when scheduling the appointment. If the provider suggests a pelvic exam, it’s okay to ask why and to share any concerns. Be open about your child’s needs, especially if accommodations might help them feel more comfortable. If a pelvic exam is necessary, you can:

- Explain the procedure to your child ahead of time and encourage questions

- Have the doctor talk your child through the procedure, if helpful

- Bring distraction tools or comfort items, such as a device that plays their favorite TV show or fidget spinner

It’s also important to know that there are many hormonal birth control options, and not all involve taking a pill every day. Depending on your child’s preferences, abilities, and medical needs, your provider might discuss:

- Patch – Worn on the skin and changed weekly

- Injection – Given every 3 months

- Vaginal ring – Inserted monthly; may require caregiver support depending on comfort or motor skills

- Hormonal IUD – Inserted by a provider and lasts several years

- Implant – A small rod placed under the skin of the arm, lasts for several years

Talking through these choices with a knowledgeable provider can help identify the best fit for your child. Remember: your voice as a caregiver matters in this conversation, but your child’s comfort and preferences are key too.

10. Keep an Eye Out for Vitamin and Mineral Deficiencies

Our Community Advisory Committee noted several anecdotes of changes in behavior related to vitamin and mineral deficiencies associated with menstruation. One example was the development of pica, an eating disorder in which a person compulsively swallows non-food items. A key mineral to keep an eye out for is iron, sometimes shown as Fe. Please speak with your child’s doctor about checking iron levels and following up with supplementation as necessary. Some symptoms of iron deficiency anemia include:

- Unusual tiredness or lack of energy

- Rapid heartbeat

- Shortness of breath or chest pain

- Craving for ice or clay, which is a sign of pica

- Brittle nails

- Hair loss (American Society of Hematology, n.d.)

Please note that some of these symptoms might be caused by existing medications. Keeping an eye out for any new symptoms is a good way to identify a need for testing iron levels, as well as other vitamin and mineral levels.

Conclusions

Menstruation is an important moment in your child’s life and can be a scary transition for both you and your child. Luckily, there are several ways you can prepare yourself and your child to successfully navigate this time.

Early, frequent, and frank education helps to establish you as a trusted source of information. Initiating conversations well in advance of menstruation helps to prepare both you and your child, and gives them time to process and ask any questions. If you don’t have an answer, don’t be afraid to engage other members of your community. Whether that’s other parents, your child’s doctor, therapists, or teachers, leaning on your community for support will ensure that you and your child are getting the most comprehensive information and support possible.

Tracking your child’s cycle, especially in the first few months, is important. This might include noting any changes in mood or behavior, seizure activity, or any other changes you might notice. If your child is able, encourage them to participate in this process, so that they can make associations between their cycle and the changes they are experiencing. Using an app or physical calendar is a good way to build in a visual component. Always raise any concerns that you or your child might have with their doctor, especially unusual or abnormal pain.

Finally, don’t be afraid of trial and error. You cannot always predict what will work best for your child. Whether that’s menstrual products, new coping strategies, hormonal birth control methods – there is no correct answer. This journey is highly individual, and it should always center your child’s needs and health. Remember that you are your child’s best advocate, and leaning on your and their support system will help you both to navigate the process successfully.

Finally, don’t be afraid of trial and error. You cannot always predict what will work best for your child. Whether that’s menstrual products, new coping strategies, hormonal birth control methods – there is no correct answer. This journey is highly individual, and it should always center your child’s needs and health. Remember that you are your child’s best advocate, and leaning on your and their support system will help you both to navigate the process successfully.

We hope that this resource is helpful. Below are appendices with additional resources.

We welcome any and all feedback on this resource, and would love to know if there is something else you would like to see here, including any information you found particularly helpful. Please fill out this survey!

Acknowledgements

In creating this resource, the Simons Searchlight team constructed a framework based on thorough research to find gaps and prioritize information. We thank Amanda Jacobs, M.D., chief of adolescent medicine at Boston Children’s Hospital, Cora Taylor, Ph.D., co-principal investigator of Simons Searchlight and clinical psychologist at Geisinger Autism & Developmental Medicine Institute. They were both interviewed for this guide. We also thank Keely Lundy, Ph.D. candidate and SFARI-funded researcher at the University of New Mexico who consulted on this guide. We appreciate Wendy Chung, M.D., chief of pediatrics at Boston Children’s Hospital and co-principal investigator of Simons Searchlight for reviewing this resource. Finally, we give a huge shout-out to our Community Advisory Committee members, April Canter, Alida James-Fenner, Christie Abercrombie, Alexandra Lee, Cheryl Richt, Rebecca Dolan, Amy Fields, Delf, Genesis Romo-Raudry, and Stacy Hanna, for their help and support in curating this resource and truly being the voice of our community.

Simons Searchlight team members Alisha Sarakki, Gabrielle Burkholz, Jennifer Tjernagel, Erica Jones, Astrid Rasmussen, Emily Palen, Matt Armstrong and Juanita Florez-Bedoya were instrumental in developing and curating this resource. We also thank Theresa Singleton and Daniel Alexander for their review and design of this guide.

Additional Resources

Appendix A: Disability-Focused Women’s Health Clinics in the U.S.

Massachusetts

Pennsylvania

Michigan

New York

- NYU Langone Health Initiative for Women with Disabilities

- Rochester Regional Health Gynecology Care Center for Women with Disabilities

Appendix B: Additional Resources on Menstruation

- Online forums

- Reddit threads provide anecdotal information from people with similar circumstances

- The Autism-Friendly Guide to Periods

Citations

- Allen, B., & Miller, K. (2019, June 4). Physical development in girls: What to expect during puberty. HealthyChildren.org. https://www.healthychildren.org/English/ages-stages/gradeschool/puberty/Pages/Physical-Development-Girls-What-to-Expect.aspx#:~

- American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. (2015). Menstruation in Girls and Adolescents: Using the menstrual cycle as a vital sign. Committee Opinion No 651. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 126(6), e143-e146. https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/committee-opinion/articles/2015/12/menstruation-in-girls-and-adolescents-using-the-menstrual-cycle-as-a-vital-sign

- American Society of Hematology. (n.d.). Iron-Deficiency anemia. https://www.hematology.org/education/patients/anemia/iron-deficiency

- Breast Development. (n.d.). In Encyclopedia of Children’s Health. http://www.healthofchildren.com/B/Breast-Development.html

- Cedars Sinai. (n.d.). Catamenial Epilepsy. https://www.cedars-sinai.org/health-library/diseases-and-conditions/c/catamenial-epilepsy.html

- Clay, R. A. (2023, July 31). PMS vs. PMDD: What’s the difference? American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/topics/women-girls/pms-vs-pmdd

- Cleveland Clinic. (2024, August 26). Puberty: Tanner Stages for Boys and Girls. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/body/puberty

- Cucci, D. (2024, May 15). Understanding cycle syncing. NewYork-Presbyterian. https://healthmatters.nyp.org/cycle-syncing-how-to-understand-your-menstrual-cycle-to-reduce-period-symptoms/

- Epilepsy Foundation of America. (2019). My Seizure Calendar. https://www.epilepsy.com/sites/default/files/atoms/files/720MSC_MySeizureCalendar_05-2019.pdf

- Halbreich, U., Borenstein, J., Pearlstein, T., & Kahn, L. S. (2003). The Prevalence, Impairment, impact, and burden of Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder (PMS/PMDD). Psychoneuroendocrinology, 28(Suppl: 3), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0306-4530(03)00098-2

- How to buy period products with your HSA/FSA Insurance. (2021, July 28). Period Nirvana. https://shop.periodnirvana.com/blogs/period-shop-blog/how-to-buy-period-products-with-your-hsa-fsa

- Ignite Healthwise, LLC Staff. (2024, April 30). Female Reproductive System. New-York Presbyterian. https://content.healthwise.net/resources/14.5/en-us/media/medical/hw/h9991281_001.jpg

- Johns Hopkins Medicine. (n.d.). Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder (PMDD). https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/premenstrual-dysphoric-disorder-pmdd

- Kaunitz, A. M. (2024). Patient education: Hormonal methods of birth control (Beyond the Basics). UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/hormonal-methods-of-birth-control-beyond-the-basics

- Lundy, K. M., Fischer, A. J., Illapperuma-Wood, C. R., & Schultz, B. (2024). Understanding autistic youths’ menstrual product preferences and caregivers’ product choices. Autism, 29(2), 447–461. https://doi.org/10.1177/13623613241275280

- Maguire, M. J., & Nevitt, S. J. (2019). Treatments for seizures in catamenial (menstrual-related) epilepsy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 10. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd013225.pub2

- Mayo Clinic. (2019, January 19). Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder: different from PMS? https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/premenstrual-syndrome/expert-answers/pmdd/faq-20058315

- Mayo Clinic. (2022, February 25). Premenstrual syndrome (PMS). https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/premenstrual-syndrome/symptoms-causes/syc-20376780

- Menstrual cycle timeline. (n.d.). Loma Linda University Center for Fertility and IVF. https://media.lomalindafertility.com/Ovulation-menstruation-chart-768×639.jpg

- Miura, T., & Hashimoto, S. (2023). Effects of Sub-Threshold Neurodevelopmental Traits on the Adjustment of Female Students to High School: A Study Focused on Premenstrual Dysphoric Mood. Journal of Developmental Disabilities Research No. 1, 61–71. https://www.jasdd.org/JDDR/PDF/JDDR01_P03.pdf

- Quint, E. H., O’Brien, R. F., Braverman, P. K., Adelman, W. P., Alderman, E. M., Breuner, C. C., Levine, D. A., Marcell, A. V., & O’Brien, R. F. (2016). Menstrual management for adolescents with disabilities. PEDIATRICS, 138(1). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-0295

- Seattle Children’s Hospital. (2025, January 25). Breast Symptoms-Child. https://www.seattlechildrens.org/conditions/a-z/breast-symptoms-child/

- Sreenivas, S. (2025, April 28). What is period underwear? WebMD. https://www.webmd.com/women/period-underwear

- Steward, R. (2018, September 18). Autistic people and menstruation. National Autistic Society. https://www.autism.org.uk/advice-and-guidance/professional-practice/menstruation#:~:text=Being%20autistic%20of%20course%20can,using%20sanitary%20towels%2Ftampons

- Taylor, C. (2022, August 31). Preparing for Puberty in Children with Autism [Video]. SPARK. https://sparkforautism.org/discover_article/webinar-puberty-autism/

- Tracy, J., Grover, S., & Macgibbon, S. (2016). Menstrual issues for women with intellectual disability. Australian Prescriber, 39(2), 54–57. https://doi.org/10.18773/austprescr.2016.024

- Office on Women’s Health. (2025). Premenstrual syndrome (PMS). https://womenshealth.gov/menstrual-cycle/premenstrual-syndrome

- Vanderbilt Kennedy Center. (2021). Healthy Bodies for Girls: A Parent’s Guide on Puberty for Girls with Disabilities. In Healthy Bodies Toolkit (pp. 3–3). https://vkc.vumc.org/healthybodies/files/HealthyBodies-Girls-web.pdf